Many will insist that Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 U.S. presidential election because of gender. They will argue that both implicit bias and toxic misogyny doomed her candidacy and that her physical appearance, voice, gestures, and manner were unacceptable to the electorate as markers of a political sovereign either because they conformed to normative gender expectations or because they violated them.

Many will assert that Clinton lost because of technology and that it was impossible for her to survive a series of scandals related to an FBI investigation of a private computer server located in the basement of her home and to the hacktivist interventions of Wikileaks, which bombarded the public with an endless stream of purloined email trails tied to “Crooked Hillary” that seemed to show a practitioner of the dark arts of insider politics and gaming the system. According to the logic of focusing on technology rather than gender, either her secretive wizardry or her sloppy vulnerability disqualified her from office.

I am going to claim that it might be precisely a conflation of gender and technology at work in the popular imagination that is to blame for her stunning defeat, which neither pollsters nor pundits predicted.

Obviously I am not the first one to suggest that gender and technology are closely allied, given the work done by previous feminist scholars in FemTechNet. For example, Anne Balsamo’s Technologies of the Gendered Body argued that gendered bodies were always “product” and “process” (3). In Technofeminism Judy Wajcman declared that “[t]echnology is both a source and a consequence of gender relations” (7). By following Beth Coleman‘s argument about “race as technology,” many would characterize gender itself as a technology.

As a scholar of gender and technology, I am interested in the long histories of this topic and how computational privacy may be conceptualized as either masculine or feminine. In my first book Virtualpolitik I argued that it was no accident that the “girl” was such an important figure of speech in so many founding documents written by the pioneers of computer science. For example, Warren Weaver in the introduction to Claude Shannon’s The Mathematical Theory of Communication compared an “engineering communication theory” to “a very proper and discreet girl accepting your telegram,” because she “pays no attention to the meaning, whether it be sad, or joyous, or embarrassing,” given the expectation that “she must be prepared to deal with all that come to her desk” (27). As an engineered series of protocols, Weaver’s girl is devoid of affect in her protection of privacy. Because her labor is feminized as service work, she is disinvested from the information she conveys and is able to be a vestal virgin uncontaminated by the content she transmits.

Jeannie Suk poses a hypothesis that “privacy is a woman” in the discourses of American technology law in interpreting Kyllo v. United States, a case in which the government used a thermal imaging device to secure a search warrant for a man growing marijuana inside his house. In the final Supreme Court decision Justice Scalia speculated that the heat-sensing device might well disclose intimate information—such as “at what hour each night the lady of the house takes her daily sauna and bath.” Suk is struck by the premises of Scalia’s example, which draws upon very old tropes, including biblical stories about Bathsheba and David or Susanna and the Elders.

Justice Scalia does not imagine merely any detail of the home, but a woman, specifically a “lady.” And speaking of “the lady of the house” implies her counterpart, the master of the house. This anachronistic language thus calls to mind more than the privacy interests of a lady bathing. It also evokes the privacy interest of the man entitled to see the lady of the house naked and his interest in shielding her body from prying eyes. Privacy is figured as a woman, an object of the male gaze. (488)

What does the confluence of privacy, gender, and technology reveal about the investigation of Hillary Clinton? And why was her use of email so damaging in the court of public opinion? The victory of Donald J. Trump — a man who refused to participate in the backchannel of email and only used the front channel of Twitter — may indicate that popular sympathies favor attacking Clinton because of her affiliation with digital secrecy.

It might sound plausible to defend a general right to privacy irrespective of condition. When Stanford law professor and transparency advocate Lawrence Lessig read disparaging remarks made by the Clinton campaign about his own bid for the presidency, he refused to condemn his embarrassed detractors. “We all deserve privacy. The burdens of public service are insane enough without the perpetual threat that every thought shared with a friend becomes Twitter fodder.”

Yet, in defending her own personal privacy Clinton claimed feminine privilege by describing many of the more than thirty thousand emails that were deleted as not pertinent to the government’s inquiry because they were about her “daughter Chelsea’s wedding, her mother Dorothy’s funeral, her yoga routines and family vacations.” All of these items depict Clinton assuming traditional female roles as a caretaker of the home and family or manager of the rituals of birth, marriage, and death. Even the yoga routines suggest activity in an all-female sanctuary. These explanations were widely ridiculed by her opponent, his surrogates, conservative news organizations, and Internet meme generators in the alt-right community.

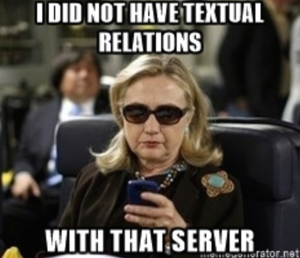

Certainly critics of visual culture watching the television coverage of Clinton’s email scandal on Fox News might be quick to observe a particular pattern. When anchors discussed her use of emails, the B-roll showed a montage of images of Clinton on her Blackberry, and some reporters spoke in front of screens with these images. The images were not flattering. They generally showed Clinton as a multitasker who was simultaneously absent and present. Often in these images of Clinton as a user of ubiquitous technologies she is ignoring other people or expressing negative affective states like irritation or boredom. In one of the most commonly used images on Fox News in which her eyes are completely veiled by sunglasses, she seems completed withdrawn from her environment.

Obama as a president has been much more savvy about avoiding the appearance of digital distraction and multitasking with others present. Official White House photographs emphasized that Blackberries should be checked at the door before important meetings, and Obama was often shown using one only outside of the Oval Office and far from the official spaces of statecraft. The Blackberry was clearly a device for outside. The sanctioned Flicker photostream emphasized a visual rhetoric of Obama checking Blackberry messages outdoors, offstage, behind his shoes, or in the dead of night.

The association of Clinton’s computer practices with impurity was also facilitated by both implicit and explicit comparisons with her husband and his infidelities and misrepresentations. A popular Internet meme showed Hillary Clinton’s image juxtaposed with typography that read “I did not have textual relations with that server,” which echoed Bill Clinton’s famous line to the American people: “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.” The meme suggests that former Secretary Clinton is denying her own digital promiscuity and lack of discursive self control.

As Wendy Chun points out any vision of digital privacy perpetuates blind spots about how computers actually work, and the dialectic of freedom and control associated with interactive media and distributed networks represents a form of false consciousness that denies the agency of smart objects, the interdependence of machine-to-machine communication, and the fact that digital discourse always involves a public machine.

In our current environment the cultural conversation in the United States seems to be increasingly about digital exclusivity rather than digital privacy. Exclusivity assumes availability but limited access, commitment rather than community. Digital exclusivity might be best-represented by multi-tier Internet speeds or variable pricing on data plans. It could be argued that exclusivity is at the heart of the entire Trump brand.

As Clinton explained in a news conference on March 10, 2015 “I opted for convenience to use my personal email account, which was allowed by the State Department, because I thought it would be easier to carry just one device for my work and for my personal emails instead of two.” Clinton’s well-documented desire not to carry multiple smart phones to facilitate mutually exclusive communication with either the State Department or friends and family violated basic code and what may well be the new direction for digital policy in many ways.

Recent reporting by Politico.com on “What the FBI Files Reveal about Hillary Clinton’s Email Server” analyzing nearly 250 pages of interviews and reports available through the Freedom of Information Act shows that her one-device/two-accounts explanation may have been much more plausible than it seems. Despite the depictions of her as a digitally immersed cybercitizen, it appears that Hillary Clinton’s textual relations with computational media were maladroit and tentative rather than seductive and practiced. Her preference for one device indicated attachment to an outdated Blackberry with a trackball, and her use of multiple email accounts was a workaround that compensated for State Department network limitations.

The Politico reporting also reveals that Clinton was unable to use a desktop computer, an account confirmed by my own interviews with State Department insiders several years ago. In the dramatization of the Politico story by NPR’s This American Life, you can hear the astonishment of reporters about her lack of familiarity with basic office equipment: “I can get not knowing how to play an Xbox or virtual reality machine or something like that, but I mean a desktop computer I mean this is literally the oldest piece of personal technology available to us today.”

According to the Daily Mail, she was also a poor typist. It is strange to think that one of the oldest of the new media practices identified by Friedrich Kittler, typing, would be the Achilles heel for a twenty-first century would-be commander in chief. Yet as a tacit knowledge practice and a form of embodied cognition, typing remained alien to Clinton.

Of course, in relatively recent memory, typing has also been a practice that is highly gendered as well. After all, J.C.R. Licklider famously wrote that “One can hardly take a military commander or a corporation president away from his work to teach him to type.” In Clinton’s aspiration to escape the conventional gender roles of secretary or office girl and dream of life as an executive or commander she somehow never acquired the basic skills of the service sector. In contrast, analysis of Obama’s hands on the keyboard indicate a well-trained typist.

Despite Obama’s basic competence in office computing practices, I argue in an article that the visual rhetoric of the White House shows it was important to defend his masculinity by distancing him from feminized computational labor practices associated with the service industry to present himself as the kind of leader Licklider describes. On the rare occasions when he is posed in front of someone else’s computer screen, as he does for the launch of a new government website, official captions on the Flickr photo stream inform us that these interactions with a desktop computer often take place near the desk of his personal secretary, Katie Johnson. Sometimes the computer screen in front of Obama’s gaze is even blank. When he “looks overhis prepared remarks in the Outer Oval Office,” the viewer can see that Obama is engaged with a traditional print text on the desk in front of him, and the neglected computer screen has reverted to displaying a neutral screen saver with the official White House logo. If we see Obama’s hands on an actual keyboard, taking part in a form of manual labour usually attached to the White House’s female employees, a caption informs us that Obama is only typing “last-minute edits” rather than engagingin extended composition that would require long-term periods of word-processing input or data entry. In another image, the detachment of a masculine president from the scene of women’s work and the computer screens of a feminized service economy is dramatized in an image of Obama catching a football pass with Johnson’s computer screens in the foreground. Obama’s eyes are on the ball in mid-flight; the information on the monitors is intended for the gaze of others.

As comedian Samantha Bee noted in a humorous routine with Sarah Paulson, “Pls. print” was one of Clinton’s most common directives. Unpacking the rhetoric of stories with titles like “Clinton directed her maid to print out classified materials” reveals multiple layers of concern about class, gender, and national security. Ironically Donald J. Trump apparently also asks his staff constantly to print out materials for him to peruse. Each morning he directs his underlings to produce on paper the top results returned after inputting his own name into the search engine for Google News.

I tend to be skeptical of generational myths about technology, but I suppose one could argue that this is as much a story about age as a marker of technological competency as it is about gender. But if that was the case why was Clinton punished for her lack of fluency so much more harshly than Trump?

Donald Trump’s Twitter feed indicates that his online persona uses two devices with one account. A Samsung Galaxy produces the angrier tweets that seem to come from him personally, and an iPhone emits more positive messages that are probably written by a PR staffer. Somehow this kind of digital promiscuity is excusable.