Contemporary Internet critics often disparage terms like “cyberspace” because they perpetuate a topographical model of digital culture that doesn’t map to the posthuman architectures of infrastructures or the designs of protocols. That said, the recent election of Donald J. Trump as president of the United States makes new demands on the field to consider how appeals to conservative values represent specific kinds of reactionary cultural imaginaries about media technologies. The Saturday evening keynote session at Transmediale, where the “ever elusive” theme encouraged presenters to ask questions about “who or what” might be acting as an agent in a given interaction was devoted to analysis of the rise of the American alt-right. Whether talking about the Trump campaign dominating the attention economy or exploiting the prevalence of filter bubbles, dystopian urbanism could be useful as a paradigm, according to those at the podium.

Richard Grusin opened his talk on “Never Elusive: The Evil Mediation of Donald Trump” by explaining why he had changed course on his original plan to discuss Facebook Live and the nature of its supposedly unmediated character. He challenged the festival’s central trope of media’s elusiveness and pointed to its origins in fantasies of immateriality. In examining the “radical mediation” and “remediation of government” of the Trump ascendancy, Grusin also argued that the “affectivity of premediation” does not disappear, just as mediation “in the middle” produces subjects and objects rather than exist as neutral matrix between them.

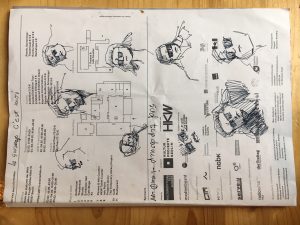

Grusin observed that Trump’s 1980s self-promoting and self-congratulatory narrative about his success as a real estate mogul of neoliberal innovation and urban renewal depended on a small investment of capital and a mastery of the dynamics of leverage and risk. Similarly Trump invested very little in advertising buys for his own campaign and relied on the estimated two to five billion dollars worth of free media that he gained from a paltry initial stake that often consisted of little more that “live tweeting television viewing.” In this way he managed to “redevelop” entire “media neighborhoods” with 140 characters of text.

Much like the algal blooms in the canals of Venice and prescient depiction of Trump’s invasive televisual transversality described in Felix Guattari’s Three Ecologies, the Republican candidate managed to colonize the social media landscape and consume all the available resources.

Grusin also asserted that those who opposed Trump – even passionately – participated in bringing him to power. Trump’s name may have served as a powerful metonym from the start, and his strategy of psychological operations – much like the LRAD sonic cannons used to disperse protesters at Zuccotti Park – may have demonstrated his mastery of what Matthew Fuller and Andrew Goffey have called “evil media.” But these factors alone were not sufficient to secure Trump’s election, according to Grusin. The morbid fascination with the spectacle of Trump realized his presidency, and the existence of polls that claimed to represent some informational reality only repressed conscious acknowledgement of complicity.

Wendy Chun delivered a talk titled “Ever Elusive? Habits and Homophily,” which suggested that “birds of a feather get killed together.” Using a comparison to climate change, she argued that there was a substantive difference between “what eludes perception and eludes analysis.” She also pointed out the roots of “elusive” in its playful ludic etymology and also justified her decision to address her topic (the structure of social networks) with technical specificity. She asserted that the history of adopting user friendliness was not an innocent one, given how WYSIWYG interfaces were intended to facilitate “direct manipulation” in the words of one of the field’s pioneers Ben Shneiderman.

Chun also recapped the thesis of her latest book, Updating to Remain the Same, that “new media matter most when they seem not to matter at all,” particularly when “habit lets us ignore the environment” in a situation where most online citizens have been “sorted into neighborhoods by intense likes and dislikes.” To recount the longer narrative of the Trump ascendancy, she cited neoliberal capitalist Milton Friedman on the value of crisis – because it is not about “what crisis is Trump provoking, but what have all these crises made predictable.” She also led through her larger argument about how current inhabitants of filter bubbles might learn something from the history of segregation and how “homophily moved from problem to solution.”

Although scholars of social networks normalize or naturalize the aggregation of like-minded individuals, Chun wanted to draw her audience’s attention to the diversity of materials that actually travel across their inherently promiscuous machines, because “a monogamous network computer would be would be a dysfunctional one.” (As a homework assignment that would demonstrate the truth of her assertion, she recommended typing a “sudo tcpdump -i en0” command to see all of the invisible and heterogeneous traffic.)

The perversion of evolutionary thought that casts the emergence of homophily as inevitable wasn’t her only target. She also wanted to draw attention to how often the term “media ecology” was romanticized as though media ecosystems were unquestionably benevolent and likely to promote harmonious, egalitarian, and sustainable environments of homeostasis and happiness. (As someone hired as a theorist for a “new media ecologies” position at my current institution, I tend to agree.) Instead Chun asserted that we “need to think through” our “fetishization of ecology” and admit that it is “kind of nasty,” because its roots come from the same source as economics, and its research depends on constant surveillance of their subjects with GPS. In other words, “ecology is like 1984 for Bambi.”

In understanding how the “improbable can become viable,” Chun walked her audience through a literature review of scholarship on homophily starting with McPherson’s much cited work on how similarity breeds connection in human ecology. She expressed her concern that network science was often misread through “outdated sociology” that propagated through different disciplines and that these distortions of findings about homophily naturalized segregation. For example, works like Easley and Kleinberg’s Networks, Crowds, and Markets claim to cross many academic fields. At the same time she noted that Lazarsfeld and Merton’s 1954 work on friendship might be more insightful than the research done by those who use it today and that the scientists who coined the term heterophily in their discussions of homophily better understood its values. She insisted that this pernicious tendency might not just predict but create unjust conditions for marginalized individuals, as a “heat list” of potential suspects in Chicago inspired by Andrew Papachristos proved to do.

A Pinboard post on how “machine learning is like money laundering for bias” summed up Chun’s concerns about how this “retrograde version of identity politics” was being sustained and perpetuated. In fact, a user “doesn’t have to click on” content “to be tracked,” according to Chun, because merely hovering over clickbait might still allow the data harvesting that facilitates homophilic sorting processes. She insisted that we should give more value to “unidirectional” expressions where we don’t expect to be liked back, and she even lauded “indifference” as the basis of cities.

(Many years ago, I first encountered the writings of Jane Jacobs under the tutelage of Julia Lupton and learned to question the heroic invention myths of Robert Moses’s urban renwal and value the disinterested sociality and heterogenousness of cities. For more illustrations and visualizations of the principle’s of Chun’s talk, check out Nicholas Gessler’s page on Segregation and Assimilation.

In the question and answer session Chun championed “networks of indifference,” and suggested that art could “keep alternatives alive.” Although she is a critic of technosolutionism, she also encouraged the development of “a more democratic search engine” that might reward heterophily more than current Google algorithms do. Grusin reminded the audience about Benjamin’s work on test performances in understanding the Trump phenomenon. He also argued that Americans tended to vote for the most mediagenic president and that the celebrity status of Obama did nothing to ameliorate this tendency.